In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

UCC’s Helene O’Keeffe looks at the crucial but under-appreciated role of women during the War of Independence, 1919-21

‘What did the women of Ireland do anyway?’

Lil Conlon posed this question in her 1969 memoir Cumann Na mBan and the Women of Ireland 1913-25. A founding member of the Shandon branch of the women’s republican organisation in Cork, Conlon dedicated the book to the those women ‘who rendered such gallant and heroic assistance’ during the War of Independence and of whom there had been ‘little or no mention’ in the intervening years.

Conlon was one of very few women to publish an account of her involvement in the struggle for independence. This absence of the female voice in the historiography of the period was reinforced by a paucity of archival material and an unwillingness on the part of the female revolutionaries to discuss their part in the republican campaign. The story of female participation was not so much written out of history, as never written at all. More recently, the pioneering work of historians such as Margaret Ward and Sinead McCoole has been supplemented by the flurry of research, archival discoveries and digitisation projects inspired by the Decade of Centenaries. The release of the Bureau of Military witness statements and the Military Service Pension files, in particular, allows for a more nuanced and detailed picture of the women that Conlon described as ‘vibrant living creatures, imbibed with a national spirit’.

With about 300 affiliated branches nationwide in October 1920, Cumann na mBan had developed in tandem with the IRA with a similar organisational structure to battalion level. The levels of cooperation between these branches and the local Volunteer units varied across the country. In some areas, as historian Marie Coleman points out, tensions arose when local IRA commanders failed to recognise the independence of the women’s organisation or preferred not to operate alongside its members. In most cases, however, strong familial and social ties facilitated mutual trust and support. ‘It wasn’t a case of taking orders’, said senior Cumann an mBan officer Eithne Coyle, ‘because we had our own executive and we made our own decisions. But if there were any jobs or anything to be done, the men – they didn’t order us – but they asked us to help them, which we did’.

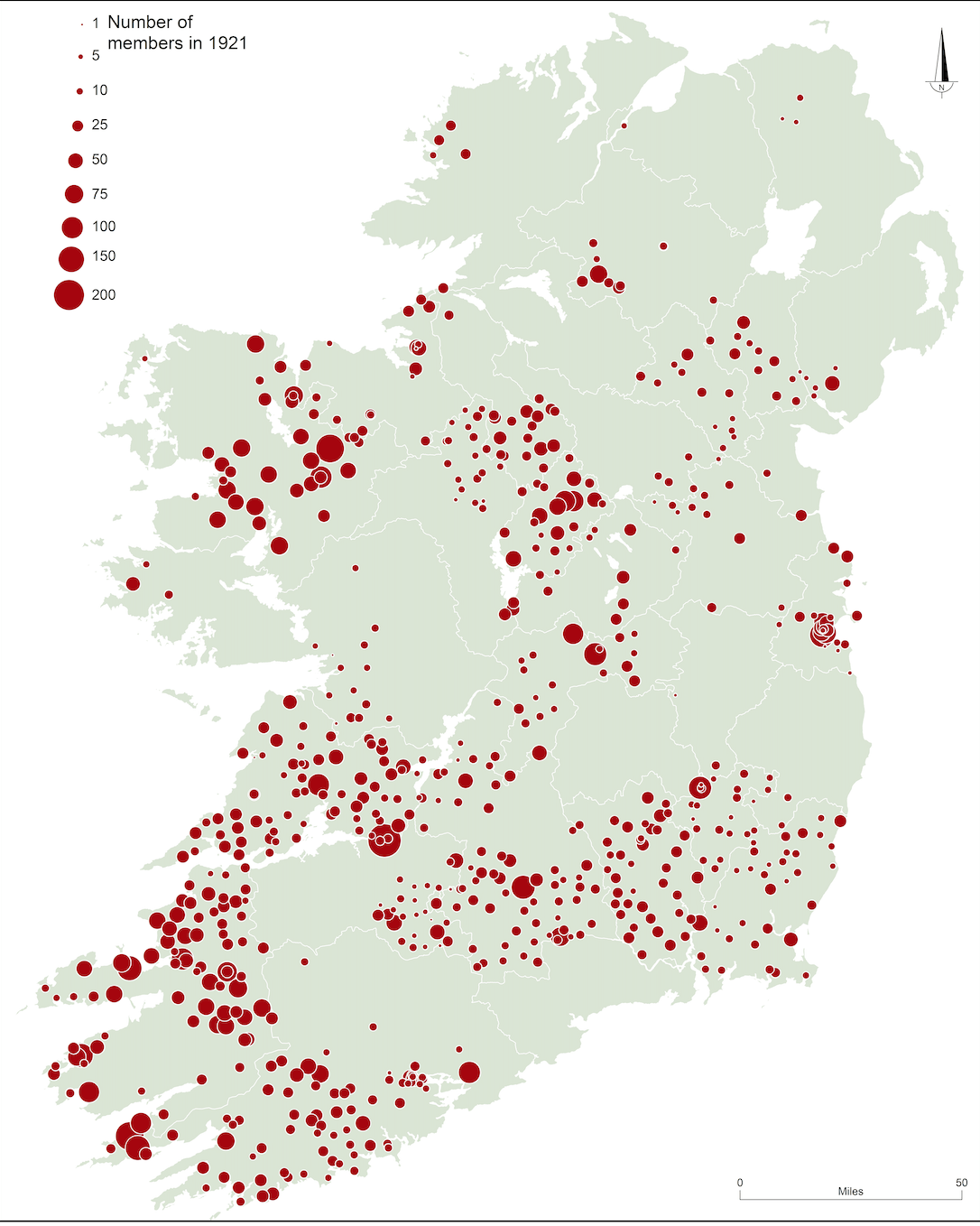

Cumann na mBan branch membership, 11 July 1921. This map comes from Military Service Pensions Collection submissions that detail 17,119 members attached to 750 branches across Ireland at the time of the 1921 Truce. Collected in 1936–37, this data is not comprehensive. Numerous district councils apparently did not submit their details (for example, west Limerick, north Cork and Waterford), while some branch lists compiled fifteen years after the conflict likely omitted certain members. Despite these weaknesses the collected data illuminates the inner workings of the female republican organisation. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution (Cork, 2017)]

The conflict between the IRA and Crown forces intensified in 1920 – a year punctuated by high profile assassinations, ambushes and reprisals. Information was a vital commodity and republican woman, organised and unorganised, formed the steel backbone of IRA communications and its intelligence network. Less likely to be searched or arrested than their IRA counterparts, the women were able to carry dispatches through enemy lines. Eithne Coyle, who reported on disposition and movement of troops in Roscommon in 1920, recalled that her ‘knees often trembled’ when pedalling past the Black and Tans, ‘especially late at night on lonely roads’.

Women who lived near RIC stations and barracks were a crucial link in the IRA intelligence chain and post office workers, such Siobhan Creedon in Mallow, played an important role in intercepting, copying and passing on to the IRA communications intended for the military and police. Republican women who worked in shops, public houses and restaurants also found opportunities to gather intelligence. Peg Flanagan, for example, ran the West End restaurant on Parkgate Street in Dublin. Because of its proximity to the RIC depot in the Phoenix Park, Kingsbridge (Heuston) Station and the Royal (Collins) Barracks, most of her clientele were members of the Crown Forces from whom she was able to elicit valuable information for the Dublin Brigade. The grocers shop in Upper Dorset Street run by her colleagues in the Central Branch, and the unassuming newsagent’s run by the republican Wallace sisters in Cork became important dispatch centres and meeting places for the IRA leadership in the besieged cities. Because Cumann na mBan’s 1920 Constitution prohibited members from ‘doing any kind of work for the English enemy’, its members were of limited use when it came to information gathering in government and military circles. Civilian intelligence operatives like Lily Mernin in Dublin Castle and Josephine Marchment Brown in Cork’s Military barracks, however, provided a vital steam of information on British Intelligence Officers, equipment, planed raids and troop movements. The value of this work was, in the opinion of Cork No. 1 Brigade intelligence officer Florrie O’Donoghue, equivalent ‘to a strong column of men’.

Parade before Lord French inspects British troops at Victoria (Collins) Barracks, Cork

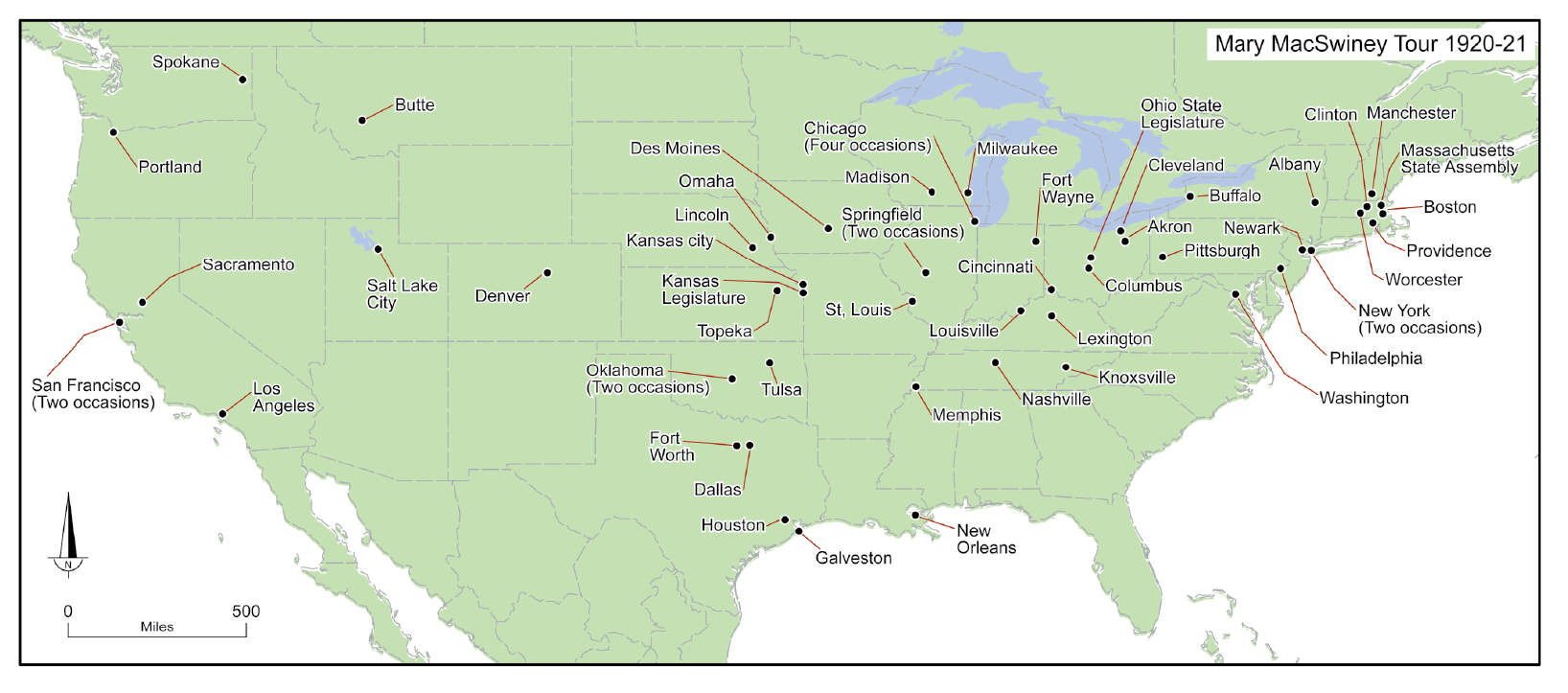

Despite being suppressed in parts of Munster during the summer of 1919 and banned nationwide in November, Cumann na mBan persevered in its propaganda efforts and maintained a visible presence on the streets of urban Ireland. As Nancy Wyse Power recorded, ‘it was felt that open activity on the part of women would help maintain public morale.’ As well as the often-dangerous work of disseminating propaganda materials, the women deputised for the men at republican funerals and when hunger strikes and executions became more common, they organised prayer vigils as a form of public protest. Senior members of the organisation also travelled to the US and Europe to highlight the increasingly desperate conditions in Ireland. During a period of eight months in 1921, Mary MacSwiney, ‘representing the Republican Women of Ireland,’ visited fifty-eight American cities and addressed over 300 meetings.

Mary MacSwiney’s eight-month tour of the US in 1921 was put together by the new American Association for Recognition of the Irish Republic (AARIR). Her major events usually drew thousands of spectators, including 8,000 in Omaha, 9,000 in New Orleans, 16,000 in Chicago, and 18,000 in Pittsburgh. She also spoke to five state legislatures, and was greeted by a parade of 50,000 supporters in San Francisco. [Source: J. Mooney Eichacker, Irish Republican Women in America: lecture tours, 1916–1925 (Dublin, 2003); Map: Atlas of the Irish Revolution (Cork, 2017)]

After the introduction of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act in August 1920 more IRA Volunteers were arrested or forced to go ‘on the run’, augmenting the increasingly-active IRA flying columns. Without the basic care provided by Cumann na mBan, their existence would have been infinitely less sustainable. The women sheltered, catered for and nursed the fugitive Volunteers at no small risk to themselves. Mary O’Neill, for example, senior member of Cumann na mBan in the very active Cork No 3 Brigade area, ministered to the Volunteers wounded at the Gaggin and Kilmichael ambushes in late 1920. Some of the women moved even closer to the military front lines engaging in dangerous activities such as scouting for the IRA during the preparation of ambush sites or road-blocking operations. ‘Here was no fragile damsel’ wrote Conlon in 1969, ‘but a cailín set in a more durable mould, attuned to the exigency of the period and eager to throw in her lot with her male companions’.

The acquisition and storage of arms and ammunition by Cumann na mBan was of extreme importance to the IRA. Peg Duggan in Cork oversaw an arms dump at her family home at 49 Thomas Davis Street and Eileen McGillicuddy’s pension file includes a hand drawn sketch of her shop in Castleisland, Co. Kerry, complete with a secret room for hiding arms and facilitating meetings of the local IRA. The women also conveyed guns and ammunition from GHQ to the regional brigades and to and from ambush sites. ‘It was nothing unusual’ for Mollie Cunningham, ‘to take two or three revolvers at a time from one company area to another’ passing by the Auxiliaries posted in Macroom Castle in the process. Annie O’Donovan of St Bridget’s branch in Cork used a pram to transport parcels of firearms across the city, while Máire Comerford ‘learned from experience that a Lee Enfield service rifle could be carried under my coat without protruding at the bottom if the muzzle was held under my ear’.

The British authorities gradually came to recognise the importance of Cumann na mBan women to the guerrilla war effort, particularly after the arrest of Linda Kearns in Sligo in November 1920 for transporting arms, ammunition and three IRA suspects. Female searchers were introduced in late 1920 and raids on the homes of prominent Cumann na mBan members became more frequent. Unlike the IRA, the women could not go on the run, leaving them exposed to threats and interrogations and later the full brutality of Crown Force reprisals. As Lil Conlon recorded, ‘swoops were made at night, entries forced into their homes, and the women’s hair cut off in a brutal fashion as well as suffering other indignities and insults’.

Fundraising for the Volunteers had been a principal Cumann na mBan activity since 1914. As well as cooking and knitting socks for the local flying column, the women in Mary O’Neill’s Bandon branch organised concerts and flag days and a weekly chapel gate collection after masses in Kilbrittain during 1920-21 period. Funds collected locally were often dedicated to providing comforts to republican prisoners – the women regularly supplementing their prison rations with parcels from the outside. Significantly, they also provided information to the prisoners’ anxious families about their whereabouts and wellbeing in the early days of detention.

Where Cumann na mBan was not directly involved with the IRA in either military or support roles, it was often in the background providing support of other kinds. Its members, for example, were central to the various relief schemes administered to victims of the War of Independence. Established in January 1921 to distribute funds raised by the American Committee for Relief in Ireland, the White Cross organisation contained a number of key Cumann na mBan personnel. At local level its members were well placed to assess the families most in need of aid as a result of the devastation caused by the war. Máire Comerford would never forget ‘calling at the homes of fighting men, or dead men, where the wives or widows were learning lessons which, too often, are behind the scenes of glory’.

To answer Lil Conlon’s question, the women of Ireland played a crucial but under-appreciated role during the War of Independence. Cumann na mBan was the most overt vehicle for female participation but civilian women too were caught up in the turmoil of those years, offering food, shelter and intelligence to the rebel army out of family loyalty or political conviction. Theirs was a specifically female brand of heroism, defined by the struggle to maintain an everyday existence in the midst of war.

– This article by Helene O’Keeffe was first published in the Irish Examiner on 2 January 2021-